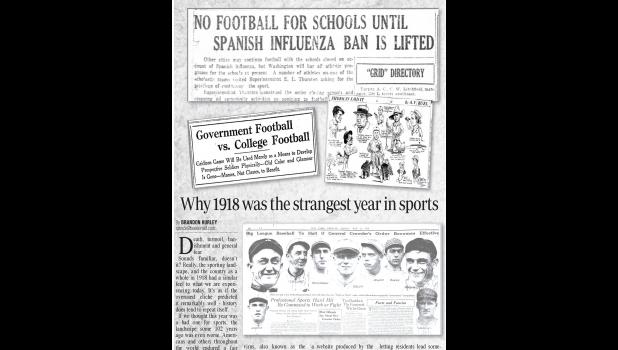

BATTLEFIELDS OF CHAOS: Why 1918 was the strangest year in sports

By BRANDON HURLEY

Sports Editor

sports@beeherald.com

Death, turmoil, banishment and general fear.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Really, the sporting landscape, and the country as a whole in 1918 had a similar feel to what we are experiencing today. It’s as if the overused cliche predicted it remarkably well - history does tend to repeat itself.

If we thought this year was a bad one for sports, the landscape some 102 years ago was even worse. Americans and others throughout the world endured a fair amount confusion and frustration, marred by shockingly similar cancellations, postponements and political arguments.

Masks were a hot topic, as was a pandemic, spectators at most events were extremely limited and athletes possessed grave concerns whether or not to take the field. A massive world war plagued much of our growing country, forcing the government to determine whether sports and entertainment were a priority (some were, some weren’t). And, not too surprisingly, they deemed almost any non-essential business irrelevant.

But, competition won over any real concerns, though fear and respect were remarkably prevalent back then. There likely were many different schools of thought on how to handle the impact of the outbreak of the H1N1 virus, also known as the Spanish Flu, while also attempting to conserve during the war.

The brutality of World War I was the ultimate disruptor, coupled with a global outbreak of the H1N1 virus in the latter half of the year, setting the tone for a stretch unlike any other. Yet, despite all the political suffering, the world managed to power through.

The H1N1 virus of 1918 was spectacularly deadly, even more so than this year’s Coronavirus. The wide-sweeping pandemic was even more deadly than today’s Coronavirus, killing 50 million world-wide, producing a “Flu ban,” which restricted athletes all over the country as well as restrictions of gatherings of any type.

Iowa’s board of health enacted a mandated quarantine on Oct. 18, 1918 according to the Influenza Encyclopedia, a website produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. The regulation banned all public gatherings, which included schools, churches, theaters and pool halls. The City of Des Moines was ahead of the curve, implementing a quarantine on Oct. 10 and eventually a spit ban. Residents could actually be arrested for publicly spitting outdoors. Joe Young, a 42-year old from Marquette, Michigan, was the first Iowan to garner a detainment for spitting on Oct. 13.

The department of public health asked residents to conduct any pertinent business promptly, avoiding lingering in groups at all possible.

The length of isolation varied throughout the state - Des Moines lifted the ban on public gatherings a little more than two weeks in, while Jefferson kept the quarantine intact for 12 weeks, finally letting residents lead somewhat normal lives in early January. The city-wide isolation guideline affected local sports, too. Like today, the regular season was greatly altered.

Jefferson’s high school football program began the year with significant optimism behind a robust roster of 19 players, the highest recorded turnout in school history. The Ramblers were set to embark on five games as the season neared. They were penciled in to take on Boone Sept. 27 (A 24-0 loss), before embarking on a long road trip, against Ames Oct. 5, at Perry on Oct. 11 (which was another shutout loss), at Denison on Oct. 18 and potential home game against Ida Grove, which was slated for Nov. 15. Two more games were scheduled at home, against Guthrie Center, Panora or Coon Rapids. The Rams were led by coaches Mr. Thompson and professor Stewart. The editors of the Bee back in the day apparently did not like using first names. The season would not last long, shuttered the day of their fourth game against Dension. By all accounts, Jefferson never finished the 1918 season, though there was no mention in the Jefferson Bee if they actually returned to the field. Due to the Jefferson quarantine, which stretched into the new year, it’s likely the players never saw the field once the “Flu ban” was enacted in mid-October.

The flu tightened its grip on the nation as the calendar dug deeper into fall. Chicago banned all outdoor sports for three weeks, lifting the ban on Nov. 4. San Francisco’s board of health actually encouraged citizens to play outdoor sports to help slow the spread of influenza, as odd as that sounds. Dr. William C. Haesler, the San Francisco health officer, urged residents to expose the virus to nature.

“One of the best preventives for the Spanish influenza is plenty of fresh air and sunshine,” he said in the Oct. 19 issue of the San Francisco examiner. “Get out in the open and play baseball.”

Whether encouraging fans and players to congregate, albeit outdoors, was a smart move, should be determined by the overall death toll of 675,000 in the United States alone, and 50 million worldwide. Leaving containment up to the local governments… hmm, interesting.

Most athletic activities, at least on the amateur and professional level, were ruled non-essential in 1918 America, but not only because of the looming pandemic but also due to the strain of the war. More than 4.5 million Americans would serve in World War I, which lasted from 1914-1918, with 116,000 dying in combat. Emotions were certainly stretched thin stateside.

College football was the most heavily hit, torpedoed by postponements and cancellations. World War I essentially obliterated the entertainment landscape, requiring citizens all over to declare for the draft. The late-surging flu pandemic also created one hell of a storm.

Several colleges produced football teams comprised of military members, the army training corps or Naval members. Couple that with many new and unusual health precautions and the college football slate was a strange one. No spectators were allowed at practices or games due to the spread of the H1N1 virus and the ensuing ban on large gatherings.

“Reports received in Chicago indicated that some of the games had been canceled because members of the teams were slightly indisposed with colds, others because of probable poor attendance due to the epidemic, and still, others for the plain reason that it is feared crowds cause a spread of the disease, despite fresh air,” read a Sioux City Journal article on Oct. 12, 1918.

The U.S. government, piloted by secretary of war Newton Baker, demanded professional and collegiate athletes stop playing and either pick up a new profession, preferably of a necessary trade or enlist in the army. It was simply that clear cut. Eventually, though often met with criticism and doubt (not unlike today), baseball and football were allowed to continue, but only if they altered their game plan, if you will.

FOOTBALL DEALT GLANCING BLOW

Football’s natural violence and intense competition became breeding grounds for future lieutenants and brave soldiers during the mid-1900s.

World War I’s residual effects were felt all over, especially in the sporting realm. The war-time draft stole a good portion of college-aged players during each of the 1917 and 1918 fall seasons, forcing the competition-starved schools to look elsewhere for talent, often calling on men who had graduated or passed up higher learning long ago. The newly-minted Students’ Army Training Corps also deployed a number of soldiers to the college teams as well, an interesting dichotomy more suited for the professional ranks than the amateur level.

Walter Camp, a well-respected journalist, compared football to battle in the 1919 edition of the Spalding Official Football Guide. He, and many others throughout the world felt the game of football helped harden future military personnel. And the various service academics often agreed, developing new, hard-trained teams all over the country.

“The mimic warfare of the gridiron proved the ideal training for the real war,” Camp wrote. “Thousands of men who, having just passed the college age, were setting themselves in business when they gave up that business to go to the defense of their country, found an opportunity in training camps and naval stations to occupy their off hours and keep in condition by once again donning the moleskin and tucking the pigskin under their arms in the old familiar fashion of their college days.”

Camp seemed fully on board with this odd revelation in which football became training grounds for soldiers who’d eventually sacrifice their lives on the battlegrounds of war. Dozens of military bases turned to football to not only train prospective soldiers, but to kill any free-time that ensued. Games sprouted up all over, forcing the country’s top referees to choose between contests.

The odd transformation of college football was met with little opposition from the national press. Various publications felt the current climate of the sport was getting a little out of hand. They thought it cost too much. A story in the Harrisburg Evening News from the October 12 edition commended the powers at hand for slowing down the expensive rise, an incredibly ironic notion seen through today’s rose-colored glasses.

“No more expensive training tables, no more hour of practice in the colleges. No more highly paid, highly specialized and highly trained coaching departments,” the paper said.

Boy, if those same writers were alive today, they’d likely burn down the entire NCAA in protest. Coaches today garner multimillion dollar contracts while many of the training departments are better equipped than most local hospitals.

College football travel was also severely limited in order to conserve fuel and time, both of which could be in high demand if the war escalated.

Yale’s Army and Navy teams met in the first college football game of the year in late October, a far cry to when the season usually starts in late August or early September.

The flu gained a significant foothold in the college athletics realm shortly after the delayed season-opener. A staggering 20 out of 30 college football contests were canceled on Saturday, Oct. 12 though half of the Big Ten’s membership decided to push on through. The shockingly brave Big Ten contests weren’t much more than exhibition games in the wake of the pandemic. Illinois took on the toughest opponent that day, as they squared off agains the Great Lakes Naval Training team while Chicago played the Chicago School of Ensigns, Wisconsin battled Ripon College and Ohio State matched up with Denison College. Minnesota clashed with a rag-tag team of all-star football players. The University of Iowa, Purdue, Michigan and Nebraska all canceled their scheduled games. Iowa was slated to take on nearby Coe College out of Cedar Rapids. Iowa managed to finish out the 1918 schedule, somehow compiling a 6-2-1 record (according to the University of Iowa). America’s favorite sport was impacted quite significantly as well, there were even doubts whether they would finish the regular season.

NEARLY KILLED IN ACTION

The late teens of the 20th century were filled with some of the most iconic names in baseball history. It was surely a shame the nation didn’t experience a full baseball slate in 1918. Babe Ruth was by far the greatest athlete in the game, and was still a member of the Boston Red Sox, but he also competed against guys like Walter Johnson and Rogers Hornsby, both future hall of famers.

Originally, Major League Baseball had agreed to shorten the regular season from 154 games to 140, though that decision was not enough to satisfy secretary of war Newton Baker. On July 1, 1918, Baker emphatically mandated a “work or fight” order, requiring all draft-eligible

American men who worked in “non-essential” fields to either enlist in the military draft or pick up a war-related job.

American League president Ban Johnson (what an unfortunate name) was fearful of Baker’s declaration and pushed strongly to keep his athletes from playing after Sept. 1. He wanted to finish the season on Aug. 20, and got six of the league’s eight owners to job on board with him. He was only interested in being a good foot soldier.

“I shall obey secretary Baker’s orders to the letter,” Johnson said in the Aug. 3, 1918 issue of the Lansing State Journal in Michigan. “I personally will not be a party to a baseball game played after Sept. 1... the government gave us our orders in declaring baseball non-essential, we are duty bound to follow them out.”

The National League, being the rebels that they were (though, they don’t seem to make many waves these days), opposed Johnson’s urging to finish in August.

Baseball’s governors campaigned hard for the continuation of the season, hoping to evade Baker’s non-essential ruling, similar to the lengths taken by professional leagues in 2020. The top defense was baseball as a sustainable business, an operation that had acquired large investors from all over the country.

Sounds oddly familiar to what the NBA, NHL, NFL and college football used as a final push. Too much money was at stake to halt action.

A few others simplified a return-to-play plan less directly. They chose to pinpoint the product on the field. The media quickly got involved in the debate, defending professional athletics during wartime. The Sacramento Bee editors described how the athletes were a special breed of humans, ones who possessed the rare skill of connecting with high speed pitches.

“Professional baseball players require a very high degree of special training and skill, procurable only by a substantially exclusive devotion of time of persons aspiring to become professional players,” the paper wrote. Essentially, the newspaper supported the professional athlete’s dedication to their craft, how they’ve likely trained their entire lives for a shot to succeed on the diamond. How it would be unfair to force them away from their life-long passion, like pushing a tenured journalist to become a brain surgeon. Of course, the comparison is not that simple, it’s rather complex, but you get the point.

“Honestly, entertainment is vital in war time and during a pandemic. Insanity doesn’t take long to creep in, and if we don’t have a safe outlet to escape to, things could get much worse before they take a turn for the better,” a columnist rebuked.

Baker eventually reversed course, changing his new order “should be so enlarged as to include other classes of persons whose professional occupations is solely that of entertaining (Sacramento Bee, July 20, 1918).” So, the league pressed on, drumming up a compromise, deciding to host the World Series a month earlier than usual.

It’s unclear what exactly changed Baker’s mind, but there were games played in September, which led to the World Series being held at its earliest date in history. The 1918 World Series began on Sept. 5, but that didn’t stop the fireworks. That particular title chase between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs was unique in many ways. The Cubs would reach the World Series just five more times over the next 98 years (never winning until 2016) while the Red Sox would endure even more pain over the next 85 years, winning the AL pennant just four times before their triumphant title in 2003. The Red Sox prevailed in the odd 1918 World Series, winning 4-2.

Unlike what we witness today, the 1918 World Series participants were determined each year in a rather simple way. Whoever finished first in the American and National Leagues would earn a trip to the fall classic. Hall of Famer Babe Ruth, largely considered the greatest baseball player of all time, won two games on the mound as the Red Sox’s ace, allowing just two earned runs in 17 innings while striking out four. It was an unusual world series to say the least, even the local newspapers took notice of the strangeness. The crowds were small and eerily quiet, clearly affected by the ongoing war. A subdued crowd of less than 20,000 fans turned out for the annual fall classic. The turnout was 13,000 fewer than the 1917 World Series game 1 between the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants. Some of this is happening today, but in the college football world. Even though LSU is limiting capacity, the southern university was struggling to sell tickets a few days prior to their home-opener.

Boxing captivated America’s hearts nearly as much as baseball and football did. A highly anticipated bout between future world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and “Battling” Levinsky was postponed in early October due to the “flu ban.” Eventually, as quarantines were lifted and rules against large gatherings loosened, the top-billed fight was rescheduled for early November. Despite the anxiety-riddled layoff, Dempsey prevailed in thrilling fashion, dominating the match before knocking Levinsky out in the third round. The “Manassa Mauler,” as he was known, would go on to become not only one of the nation’s premier boxers, but also one of the most respected athletes in the world. Dempsey held the heavyweight title for seven years, using his convincing victory over Levinsky to catapult himself to secure the belt in 1919, which he held all the way through 1926. Dempsey recorded 62 wins during that streak, 51 of which came by way of knockout.

I don’t necessarily know if there’s really much we can learn from what happened in 1918, but it’s at least worth acknowledging. As hard as I tried, I couldn’t really tie a bow on my research. There are a ton of similarities, as you can see, though it seems as if the world endured, just like we are now. Power through and sports will eventually get back to normal, right?

- Log in to post comments